Hello, here is a picture of an ostrich I met on my last day in Chad. I tried to keep this post as concise as possible and thus had to omit many details. If you are busy and prefer to read a shorter version of the story, the first paragraph is for you.

The good, the bad and the awesome:

I went to Chad in the beginning of March to help finish an Adventist Health International surgical clinic in Arqudi, Chad, the structure of which was built and designed by Hooman Fazly a couple of years ago. My colleague and I managed to finish floor casting, plumbing, all the interior plaster work, and some more. Soon the Clinic will start providing services to atleast two villages, Arqudi and Abougoudam. We were also managing the construction of the managing doctor’s private residence in a Abeche, 40 minutes away from the clinic, we managed to finish about a third of the house. Due to political trouble between officials in town we were asked to abandon the house build site before we met our goal and to restart building the house near the clinic. We were able to finish the foundation work and a little bit more of the restarted project. We developed good relations and friendships with the local workers, they decided to throw us a meet grilling party during our last week, Chadians know how to grill well. Feel free to look at the pictures below.

The details:

Here I am two weeks after returning from Chad, enjoying the comforts of civilization and wondering how things are in Arqudi, Ouaddaï, Chad. I spent a month, and a half managing finish work in an Adventist Health International surgical clinic, which Hooman Fazly had planned and built a couple of years ago. Whitey and I had also designed and started building the managing doctor’s personal residence, Dr. James Eric Appel.

I met the most dedicated and motivated workers there… It honestly shocked me to learn that tribal villagers in Chad are by far the most tolerant people I have ever met. The general attitude seemed to be that I could do whatever I wished as long as I respected the locals. Whenever I asked if a specific action was acceptable in their region, I got the same answer, “men should never preach to other men; only God has enough wisdom required to judge and correct the actions of people.” If somebody had described the level of tolerance in Chad and asked me to guess which country those tolerant people live in, I would have probably guessed one of the top 10 wealthiest countries in the world. Yet there I was in one of the world’s most underdeveloped countries. From the late eighteen hundreds until today, Chad has always been involved in some regional anti-colonial uprising, civil war, or regional conflict. When it comes to understanding Chad’s extreme underdevelopment, the former is only the tip of the iceberg when.

I had tried to find clear information about Chad before I traveled there, and the only thing that I found was the following line on Lonely planet’s website “Wave goodbye to your comfort zone and say hello to Chad. Put simply… Chad is Africa for the hardcore.” The prior genuinely reflects my experience. As if it is not enough that most of the roads are unpaved, health care is unavailable in most areas, the military controls everything, most water wells are to some extent contaminated, and the temperature is flaming high for most of the day. The intense weather rendered my laptop almost useless, which explains why I am posting a blog update weeks after returning from Chad.

On the night of 28 February 2015 my flight landed in N’djamena; an immigration officer at the airport asked me a few questions, stamped my passport, and asked me for a bribe. I refused to pay anything, and thus he smiled and let me go. Outside the airport, my host in the capital was waiting for me. He told me that he would arrange my bus ticket to Abeche in eastern Chad within a day. The host family was very hospitable and made sure that I was as comfortable as possible. Two mornings after my arrival, my host took me to the central bus station, made sure the police knew I was traveling to Abeche, and asked one of the passengers to help me if I had trouble at any military outposts on my way to Abeche. The ride to Abeche was safe, easy, air-conditioned, and troubleless, except for the last outpost outside of Abeche where the military asked me to un-board and informed me that I couldn’t return to the bus. They didn’t offer any answers to my questions, so I was worried and afraid they would send me back home, but I figured that they were friendly when they allowed me to sit with them in the shade. A few minutes later, an immigration officer came, collected my passport, and took me to the bus station where I picked up my bags and met with Abraham, our translator and worksite facilitator, and Whitey Flagg, an old friend and colleague from Cal-Earth. The Immigration officer informed me that I had to follow him to a police station. As soon as Whitey started the car to follow him, he had disappeared, so we had to drive around town for about 20 stressful minutes to find him. It turned out that he meant to order us to follow him to the immigration office… After about an hour, I was done with all the paperwork, and so we headed to Dr. James’s house, where I had dinner and slept for the night. I made sure I slept as early as possible to relax my body before I started working in the intense sub-Saharan desert.

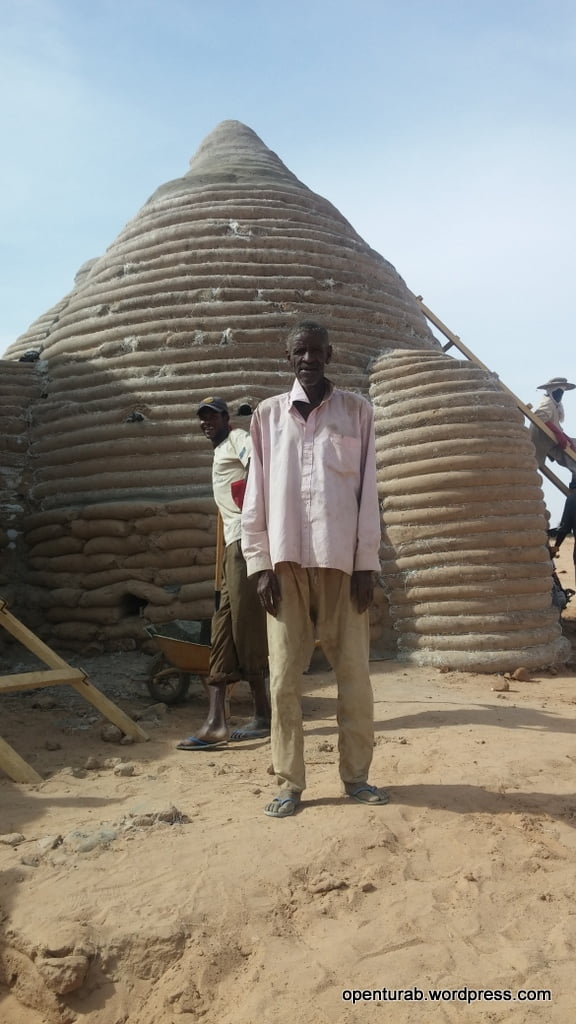

The following day Whitey and I headed to the personal residence build site, a hilltop that overlooks Abeche. We discussed different house floor plans and potential challenges, then we marked the foundations and asked Abraham to arrange to transport the workers from Abougoudam Village to the worksite. Within a week, the workers had all the foundation trenches dug, and most of the foundation bags laid. It wasn’t easy to manage workers who had never built superadobe domes before. However, the versatility of superadobe lies in the fact that it’s easy to understand its basics. So after a week and a half of bag laying, most of the workers understood how things should be done, and the work speed improved significantly.

Since I am discussing the versatile and ease of application of superadobe, I will rant about a side topic for a bit. At Cal-Earth, we were taught to measure where each bag should lie using chain compasses attached to doggy domes or pipes, in Peru Whitey had found doggy domes hard to run by and metal pipes are sometimes not worth the cost, so he decided to use a caster attached to a wooden post. In Chad, however, for some reason, casters were overpriced, and thus, we decided to tie the compass chains to wooden posts using metal strips and screws, which proved to work effectively and cost nothing. We build superadobe with this mentality; as long as you understand building principles, you can take as many shortcuts and use as many cost-saving methods as you wish. Below are some photos of our work from 3 March through 19 March.

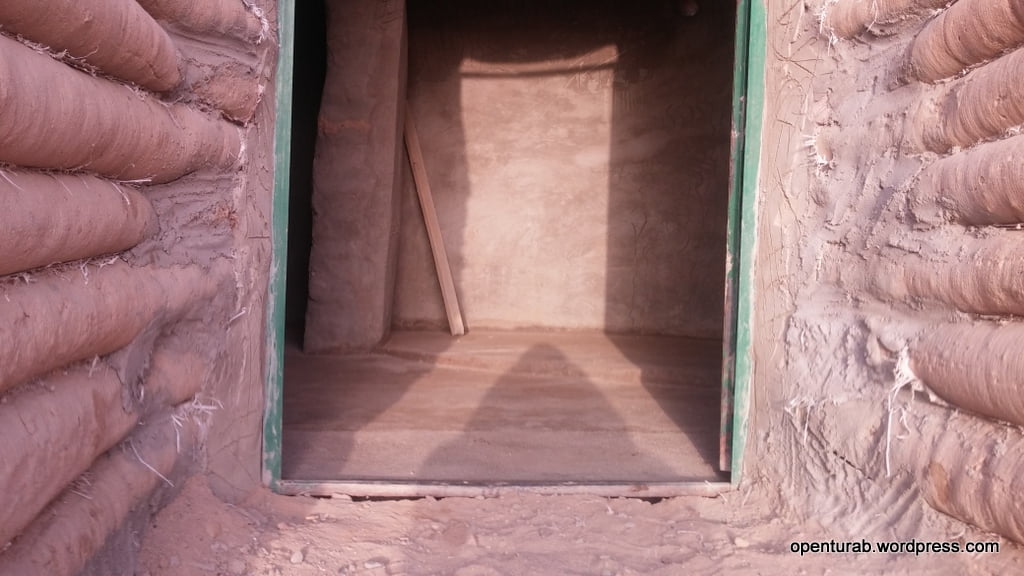

On March 14th, I moved to the Clinic build site for two days. I had gone there before to give general direction to workers on how to plasters and tackle other minor issues. However, once we reached a point where we had to cast the floors and install drainage in the domes, I had to be at the clinic permanently to manage all the details. The workers had no experience or knowledge about grading floors towards a drain or setting drain pipes below grade. Below are some photos of the clinic.

Whitey and I decided that it would be best for me to move to the clinic while he stays at the house build site for time efficiency reasons. The clinic is in Arqudi, and almost everyone there speaks Arabic, and if Whitey were going to move there, Abraham (the translator) would have to move with him. Secondly, the local government in Abeche was getting agitated that we were building on a hill that overlooks the whole town. Just four days before I moved to the clinic to start planning floor and drainage work, the construction at the residence site was paused for a few hours by the municipal police. The hilltop that we were building on was an important strategic area during the rebellion in 2008. Thus Abraham had also to stay to deal with the agitated local government. Below is a photo of Whitey taking a picture of one of many bullet casings that we found on the hill.

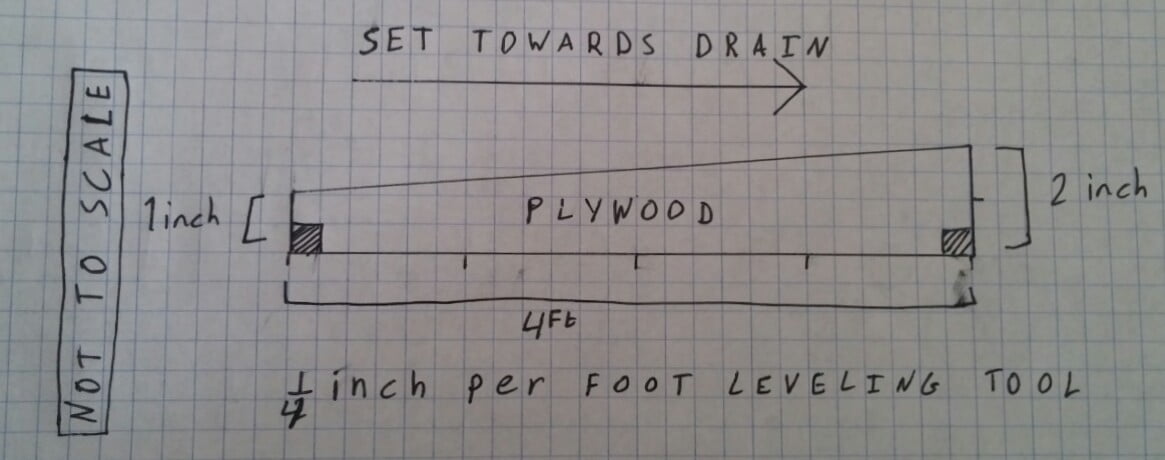

On March 19th, I returned to the clinic build site to manage drainage installation and floor casting. Below are some photos of plumbing work and floor pouring. We found that the best way of laying floors in a circular room is to cast the floor in pies that are 4ft wide at the top. Sloping the floor towards the drain could be done using a string level and a measuring tape. An easier and quicker method utilizes a piece of wood that’s cut to the desired slope, it is used by setting a beam level over the wooden implement, setting the implement over a screed, and pointing the taller end of the implement towards the drain. When the beam level is balanced, it means that your screed is set to the desired slope, ¼ inch per foot in our case. Refer to the diagram below.

By the 20th of March, the mayor of Abeche and the governor of Ouaddaï decided to halt the house construction project on the hill indefinitely. The governor had approved the building project earlier. However, due to political maneuvering by the mayor, the governor was forced to reverse his decision. Thus Whitey and all the workers at the residence building site started evacuating and moving everything to the clinic build site. At this point, we were asked to redesign the house and to rebuild it near the clinic. This was disheartening for me and Whitey since it meant that we wouldn’t be able to complete our project on the hill top and thus only meet our goals at the clinic. Below is a photo of the second house project. We couldn’t accomplish much at the second house since constructing the lowest courses of any dome are very time-consuming.

Whitey left on the second Wednesday of April, and the workers made sure that they gave him a sweet goodbye party. They grilled a whole goat during his last day. I left a few days after him. It was tough to say goodbye to all the workers after developing friendship and mutual respect. Here are a couple of pictures of me on my last day with some of our most dedicated workers.